|

| May 26, 2015 | Volume 11 Issue 20 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

NASA test materials could be part of mystery Air Force space plane cargo

Editor's note: The (no-so-top-secret) X-37B was launched from Cape Canaveral, FL, on May 20, with the Materials Exposure and Technology Innovation in Space experiment onboard.

By Karen Northon, NASA HQ, Washington, DC

The X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle taxis on the flightline in June 2009 at Vandenberg Air Force Base, CA. [Image Credit: U.S. Air Force]

Building on more than a decade of data from International Space Station (ISS) research, NASA is expanding its materials science research by flying an experiment on the U.S. Air Force X-37B space plane.

The Air Force operates the unpiloted, robotically controlled, and reusable X-37B space plane to test technology during long-duration missions. It has completed three missions launching from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida and landing at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, with the last mission ending in October 2014 after 674 days in orbit. It takes off vertically, lands horizontally, and continues to further industrial advancement for reusable space test vehicles.

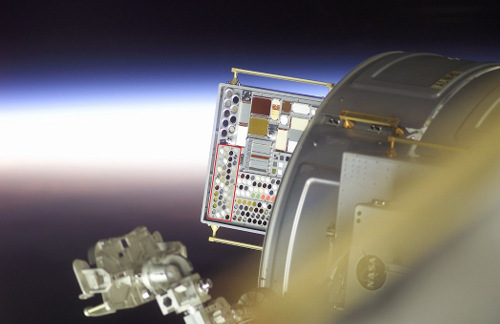

By flying the Materials Exposure and Technology Innovation in Space (METIS) investigation on the X-37B, materials scientists have the opportunity to expose almost 100 different materials samples to the space environment for more than 200 days. METIS is building on data acquired during the Materials on International Space Station Experiment (MISSE), which flew more than 4,000 samples in space from 2001 to 2013.

MISSE 2 outside the Quest Airlock on the International Space Station. The Polymer Erosion and Contamination Experiment (PEACE) experiment is outlined in red. [Credit: NASA]

"By exposing materials to space and returning the samples to Earth, we gain valuable data about how the materials hold up in the environment in which they will have to operate," said Miria Finckenor, the co-investigator on the MISSE experiment and principal investigator for METIS at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, AL. "Spacecraft designers can use this information to choose the best material for specific applications, such as thermal protection or antennas or any other space hardware."

The International Space Station is a unique orbiting laboratory used to conduct hundreds of investigations each year, with half of the research resources designated as a U.S. National Laboratory for investigations selected through the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS) to provide direct benefits to people living on Earth. NASA research focuses on advancing scientific knowledge and demonstrating technologies to enable human exploration into deep space through investigations such as the current one-year mission with NASA astronaut Scott Kelly.

It is difficult to simulate all the aspects of the space environment, so testing materials for extended durations is particularly important. Programs across the aerospace industry, including NASA's Mars Curiosity rover, the James Webb Space Telescope, and SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft have improved performance by selecting materials tested on the space station. All of the data from the MISSE investigations are available in the Materials and Processes Technical Information System, where the METIS data also will be made available.

Researchers are flying some materials as part of METIS that also were tested during MISSE. Testing the same types of materials again can help scientists verify results obtained on the orbital outpost. If researchers see different results between the same type of materials used on both METIS and MISSE, it would help scientists learn about the differences experienced in various orbital environments.

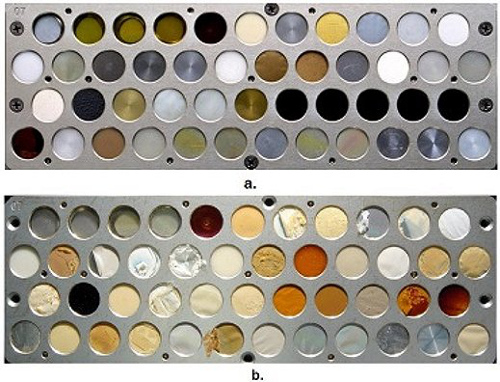

MISSE 2 PEACE Polymers experiment: a.) before flight, and b.) after four years of space exposure on the exterior of the International Space Station.

Editor's note: Look closely. Wow, what a difference. [Credit: NASA]

"When we flew newly developed static-dissipative coatings on MISSE 2, we did not know they would be used for both the Curiosity rover and the SpaceX Dragon," said Finckenor. "Some program we don't know about now will be successful because engineers found the data they needed."

The METIS experiment complements the station research, looking at a variety of materials of interest for use on spacecraft built by NASA, industry, and other government agencies. The materials flown in space are potential candidates to replace obsolescent materials with environmentally friendly options.

Finckenor leads a diverse team of investigators from other NASA centers, aerospace companies, and universities. For both MISSE and METIS, the customers supply small quarter-size samples. METIS will fly a variety of materials including polymers, composites, and coatings. Finckenor prepares the samples for flight and helps with post-flight sample analysis.

"Data from the space station and METIS materials experiments will improve the lifetime and operations of future spacecraft needed for NASA's journey to Mars," said Lisa Watson-Morgan, Marshall's chief engineer.

Marshall provided the hardware for the experiment, while the Air Force is providing NASA the opportunity to fly the experiment. The flight provides researchers an opportunity to collect additional data in advance of the next MISSE experiment aboard the space station in a couple of years.

SIDEBAR: Exposing materials to the test of time through MISSE

By Mike Giannone, NASA Glenn Research Center

Much like that pickup truck rusting in your backyard, extended stays in the brutal environment of space can take their toll on spacecraft, satellites, and space stations. In fact, anything outside the protective blanket of our atmosphere can be assaulted by orbital debris, temperature extremes, micrometeoroids, direct sunlight, and, when spacecraft are in low-Earth orbit (LEO) or orbiting near another planet like Mars, atomic oxygen. Over time, this relentless hammering by the space environment degrades many spacecraft materials.

To understand how different materials perform in LEO, researchers designed the Materials International Space Station Experiment (MISSE), a series of flight investigations mounted to the exterior of the International Space Station.

MISSE research has resulted in several improvements to spacecraft. For example, the results from MISSE 7, which concluded in 2011, improved the performance of a satellite antenna that launched in 2014 as part of a meteorological satellite.

Begun in 2001 and building on earlier degradation studies, MISSE is a multi-organizational effort that includes NASA centers, U.S. Air Force and Naval research laboratories, universities, and private industry. MISSE has flown during six different missions to test a variety of samples, ranging from materials to help develop an atomic oxygen erosion predictive tool to a new satellite antenna coating.

More than 4,000 samples and devices, such as solar cells, have flown throughout MISSE's 13-year history. The samples fit into the suitcase-size Passive Experiment Container (PEC). The container is two-sided so that samples are exposed to the space environment on both sides.

"We often use trays that have a series of openings for one-inch diameter samples," said Kim de Groh, senior materials research engineer and MISSE investigator at NASA's Glenn Research Center in Cleveland. "Imagine you have a piece of cling wrap from your kitchen, and you punch out a one-inch diameter disk. We then ask, 'Will that survive for one or more years in space?' Probably not. So we stack layers of the material on top of each other and fly that stack in space."

Samples are left in space for extended periods. For example, MISSE 1 and 2 left materials exposed to space during a four-year stretch from 2001 to 2005. MISSE 7 flew in the LEO environment for 18 months. The most recent test, MISSE 8, flew for two years. Those extended stays have helped researchers identify ways to improve materials for use in space and on Earth.

NASA materials engineer Miria Finckenor prepares to use a spectroreflectometer to analyze the reflectivity of coating samples. [Credit: NASA]

"We flew several antenna coatings for the Aerospace Corporation and they used that for the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP)," said Miria Finckenor, materials engineer at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. "The results that came from MISSE 7 made enough of a difference that they stripped off the coatings from their last two satellites to replace it with the new coating because it worked that much better."

Finckenor did the pre-flight and post-flight measurements of the coating at Marshall. The coating, developed by a team led by Donald J. Boucher, principal engineer and scientist at Environmental Satellite Systems, Aerospace Corporation, El Segundo, CA, solved an antenna performance problem.

"We had coated our main reflectors with a material that turned out to be sensitive to water over time. It changes its properties if you have it in a humid environment," said Boucher. "We decided to remove the coating from all our remaining flight units and design a new coating that was very stable with respect to water."

On April 3, an Atlas V rocket launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California carrying the DMSP-19 satellite into orbit. The DMSP-19 antenna employed the new, MISSE 7-tested coating.

"We were far less capable of describing vertical distribution of the moisture in the atmosphere with this old antenna coating," said Boucher. "And now we are much, much more capable. We fixed an entire distribution issue with this new antenna coating. All of our satellites have this new reflector coating."

The years-long testing of different materials yields answers for both the aerospace community and those wanting to optimize materials for use in Earth applications. MISSE has played a role in numerous advances, including NASA Glenn's Atomic Oxygen Erosion Predictive Tool that helps in designing new spacecraft, a coating for the Mars Curiosity Rover, a snow-white thermal protective coating for the Dragon spacecraft, and contributions to art restoration.

All of this MISSE data is now available online through a Materials and Processes Technical Information System (MAPTIS) account. When filling out the application for access, users simply indicate in the justification field that they want to view this MISSE database.

New databases, new materials, and new predictive tools lead to better, longer-lived spacecraft and satellites as well as to improvements to our daily lives here on Earth. With such wide-ranging influence, the value of MISSE data could prove to be timeless.

Published May 2015

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy